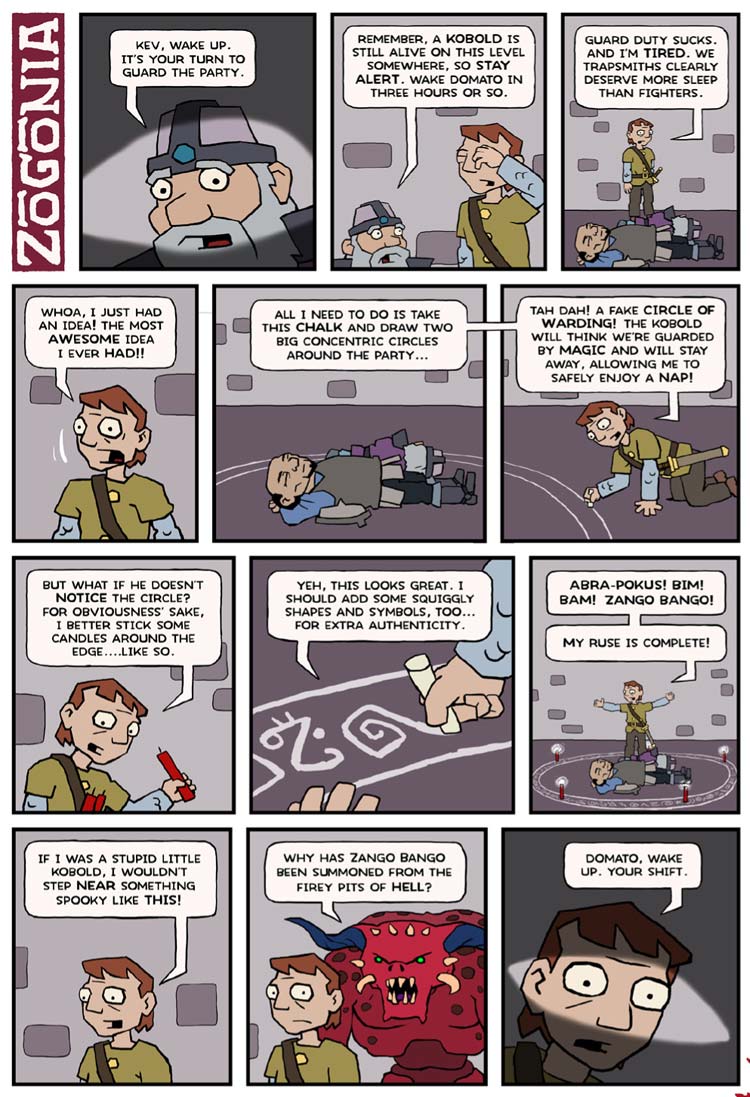

Creating a D&D 5e Character for Beginners!: Dungeons and Dragons is a pen and paper role-playing game published by Wizards of the Coast. Prior to playing a game of Dungeons and Dragons, you need to create a character. This task can be daunting, especially for new players. Below you will. Solo druid build, 1 DM 3.5e rule, and 80d6 dmg at level 5. Fall damage on the object under the trap. There’s no rule for it in 5e, so we used the one in 3.5e. In this five part series I’ll share the mistakes I have made and the things I got right when I started to build a campaign world called Vodari. The Big Picture ‘The Big Picture‘ is the first subtitle in the D&D fifth edition Dungeon Master’s Guide. When I first starting building out Vodari in the fall of 2014 the DMG had not even been. Nov 12, 2014 Shouldn't we wait until we see the entire section on Building New Races – heck, maybe the actual whole DMG – before casting aspersions on its success or failure regarding contents? We have here one page that isn't even an entity unto itself but begins in media res and ends likewise.

From D&D Wiki

| This page is incomplete and/or lacking flavor. Reason: As a community guideline, this page will forever be incomplete. Feel free to jump in and add your wisdom and insight to the community's standards!!

|

- 15e Background Design Guide

- 1.1Preload Walkthrough

- 1.1.2Roleplaying Feature

- 1.1Preload Walkthrough

So, you want to make a background? Well, you're in luck because if you want to get started homebrewing character options for 5th edition, this is one of the better places to start! Backgrounds are simple, flexible, and fun! A background can be completed within a few hours if you know what you're doing, or a couple of days if you're totally new to it. A background can also reach a completed, balanced, functional state with the efforts of only one knowledgeable editor, though some backgrounds may take the combined efforts of 2-3 people. As a fundamentally low-powered, low-crunch element of the game, they are a great place to cut your teeth and learn control and restraint. All of the design philosophies of 5th edition impact backgrounds, so they're a great place to start learning those philosophies right away, because the limited mechanics make it easier to focus on the big picture, rather than being overwhelmed by a wall of mechanical details. As with everything on the wiki, please make sure that you are familiar with the precedent, which in this case is set by the 5th edition corebooks, the Player's Handbook, (PHB) Monster Manual, (MM) and Dungeon Master's Guide, (DMG). Core character backgrounds can be found on PHB pp.127-141, and they are immediately preceded by an explanation of what they are, how they work, and how to customize them on PHB pp.123-125, starting under 'Personal Characteristics' and 'Backgrounds'. Explicit guidelines for creating a background are provided on DMG pp.289. This content is subject to The Three Pillars of Adventure (5e Guideline).

Preload Walkthrough[edit]

OK, when designing a background, you have a LOT of freedom. Let's start with the concept: what is it you are trying to represent? Remember that your background is not the same thing as, or a replacement for, a backstory. A background is supposed to represent the type of life experiences that your backstory has provided you. It isn't a backstory on its own, but is part of it. Rather, a background represents how your backstory affected your character up to this day, when they began adventuring. In other words, you could think of a background as a 'backstory type' or 'backstory class'. In psychology terms, if your race gives you special properties based on your nature, then your background gives you special qualities based on your nurture.

As a result, a background should be designed to be as open-ended and broad as possible, while still being thematically focused. And really, that's what a background is all about: what is the theme you are trying to represent here?

For the wiki, we generally prefer backgrounds be written in the style of the core rules backgrounds: generic, despite that being oppositional to the guidelines given in the DMG. The main reason for this is, as a publicly available resource, we have no idea what campaign setting any given person is going to be using! So, in the interests of providing homebrew resources that will actually be useful to your potential audience, try to strip away the setting-specific stuff and present the background in a form which is readily modified and cannibalized into other peoples' games.

This is not as draconian, or as difficult, as it may seem. Take, for example, the Battlesmith (5e Background), which describes a person who was once a member of a dwarven military order called the battlesmiths. There are no examples of this order existing in any official campaign settings, despite it seeming very specific. The thing is, it doesn't limit other races from playing a battlesmith, it doesn't specify any specific locations, characters, or history, and presents the information in a format which would allow the reader to incorporate battlesmiths into their campaign without any further reading. It contains the whole idea, and the idea is as generic as possible, that you could drop this whole concept into any campaign setting that includes dwarves. A really creative DM who still likes the idea, but has no dwarves in his setting, could even just change every instance of the word 'dwarf' into some other race, and it would still work just fine! This is what we mean when we say the background should be generic: it should be easy to incorporate it, and its surrounding ideas, into almost any setting. Generic does not mean plain or boring.

In order to make a flexible, open-ended background, try to make sure it can work for a character of...

- any gender

- any alignment

- any core race

- any core class (character class, not socioeconomic class)

Dmg 5e Pdf

Note that this does not mean detailed and specific backgrounds which could only work for certain characters or in certain settings are unwelcome. You are absolutely free to post an inflexible, setting-rich creation that you found exciting! Just be aware that, the more work someone needs to do in order to adapt your idea into their game, the less likely they are to do so.

- Good examples of a background theme include

- A profession

- A cultural heritage

- The environment they grew up in

- A specific defining incident or moment

- A unique socioeconomic status

- A unique, typically physical, quality or trait

- Examples of themes to avoid include

- Requiring a specific character option, like gender, race, Alignment, or some other mechanical property like an ability score requisite. We want to be able to use your ideas!

- Something so broad as to be nondescript, like 'person' or 'grandson'. You need to be a bit more imaginative- Give us something deeper than a puddle!

- Anything which would be better described as a race, (what you are) or class (what you do). A background is where you came from; a piece of who you are. If you find yourself struggling with writing a lot of mechanical properties, you're probably trying to shoehorn an idea into a form that does not represent it very well. We want your ideas to get their best presentation!

- Anything that is antithetical to the collaborative nature of D&D. Examples include backgrounds who would in some way harm their allies, backgrounds who are designed to hog the spotlight, backgrounds who dominate over the DM's authority over the setting, backgrounds who encourage antisocial behavior, backgrounds who mandate a character being in a position of authority over other PCs, and more. Basically, anything that exists as a blatant excuse for someone to be a jerk to the other players is not welcome here.

Consider the uniqueness of your background, both thematically and mechanically. Consider whether your idea could already be covered by a pre-existing core-rules background. They are incredibly broad and can cover most types of people in a fantasy setting. The soldier background[1], for example, can cover mercenaries, terrorists, ninja, samurai, generals, infantry, archers, knights, cavalry, and even police! Consider whether your theme can provide a better experience than trying to shoehorn the same idea into an existing background. For example, a soldier-based police officer may not be so great at investigating crimes unless the player chose a class which provided them the option of useful tool and skill proficiencies, so a dedicated 'detective' background may be a valid idea.

Consider what would happen if a character with your background came face-to-face with characters of any of the core rules backgrounds. Make sure that your idea will be socially and mechanically compatible and comparable to them, rather than thematically jarring. A sudden and distinct change in theme attached to one character can totally ruin the immersion of the group.

Consider the types of games your theme could appear in. If it's really dark and grim in flavor, then DMs who are running lighter, more fantasy-adventure or comedy games, may be distraught by a player bringing a character with that background to the table. Likewise, a highly comedic background won't be compatible with a gritty, violent campaign. That isn't to say you can't make those things, just be aware that it will reduce your audience.

So, once you have your theme clear in your mind, start writing. Give at least one good paragraph describing and explaining your theme and its scope. Then follow that with a solid paragraph of questions for the player to consider when choosing this background. The questions should cover the basics required to justify the background selection and should be phrased such that the answers will help write the character's backstory.

One edge-case exists on the wiki. Slave (5e Background) was explicitly designed to be out-of-balance in a way which disadvantages the PC. Notice that the page has a design disclaimer, justifying the imbalance as the intended purpose of the background, and warning players and DMs of the potential implications of its use.

Skill Proficiencies: Every background gets two skill proficiencies.

Tool Proficiencies and Languages: A background can provide a maximum sum total of 2 tool proficiencies and/or languages. Languages and tool proficiencies are considered interchangeable.

Equipment: The starting gear for a background (its 'loadout') can include adventuring gear and tools. Weapons and armor are not normally acceptable. The one example of a background which explicitly provides a weapon, is the gladiator variant of the entertainer background[2], which allows you to replace the instrument the background usually provides with an 'inexpensive and unusual weapon', and even then only through a roleplaying feature. (Which is poorly defined on purpose, forcing the player and DM to interact to decide what that means) An example of a background which wanders into the grey-area is the sailor background[3], which includes in its equipment, a 'belaying pin (club)', implying that, if used as an improvised weapon[4], it would have the properties of a club. Another example is the outlander background[5], which provides a 'staff', which could be interpreted by some DMs as equivalent to the 'quarterstaff' entry in the weapons list, but is not explicitly described as such. Each background should also include some starting money, typically contained in a pouch. (Though the noble background[6] provides a unique 'purse' item) The precedent sets a range of 5-25gp. Each background is responsible for providing the character with their clothing. You can use the generic outfits provided in the PHB, as most backgrounds do, or invent your own variant of such. For example, the criminal background[7] provides the player with one outfit of 'dark common clothes' without any references to such a thing elsewhere in the book! You can also create your own unique outfits, if a modified version of a core rules item doesn't fit your idea, as exemplified by Farmer (5e Background). Next, every background also includes 1-3 flavor items. These are special items with no specific mechanics which exist only in the background's equipment loadout. These include symbols of authority or allegiance, special tools, unique clothing articles, sentimental items, fashion accessories, or other knick knacks. Be careful when selecting and designing gear for the starting loadout of a background. Many adventuring tools have a TON of implicit power not written into their mechanics. For example, an animal trap may seem harmless enough, a useful tool for sure... until you consider all the things a creative player could use that trap to do, other than trap animals! Of particular importance, be very cautious in how you phrase the descriptions of your flavor items. Including too much implicit power in the exact wording of these items can cause a background to become shockingly overpowered in the hands of a creative player. The signet ring of the noble background is a prime example, if the DM is not careful about how much authority the PC's family name holds.

Specialization[edit]

Not every background includes a specialization. A specialization section is useful when you want to make a background that is so broad, it incorporates many types of things which we have other words for. In other words, it's a way of overcoming the problems generated by the excessive granularity of the English language. A great example to look to here is the criminal background[8], which includes a variety of different types of thugs. This allows it to capture all of the richness and variety it was intended to represent.

| d6 | Specialization |

|---|---|

| 1 | One method is to list different titles, names, or ranks which the character may have obtained, as seen in criminal. |

| 2 | Another method is to include a list of variant properties, like what was done for the charlatan[9]. |

| 3 | A third method, found in the guild artisan[10] lists potential group affiliations. |

| 4 | The hermit[11] lists off various goals the character was seeking. |

| 5 | But there's nothing stopping you from inventing new ways of expanding your background's horizons through a specialization section! |

| 6 | You also don't need to even have specializations, or stick to the preload limit of 6! The section is optional, and the table is editable. |

Roleplaying Feature[edit]

Every background should have a roleplaying feature; backgrounds are not just an excuse to get a couple extra proficiencies and some starting loot. Those proficiencies, and the items they come with, are intended to represent your life leading up to the start of your adventure! Your roleplaying feature is one of the most important aspects of a 5th edition character, and a defining feature that sets 5th edition apart from its predecessors. When writing a roleplaying feature, remember that a background is not a backstory. A background is a sort of 'grouping' of common backstory types which would generate very similar benefits. While a background can be used to write a backstory, they can just as easily be used to arbitrarily represent a previously written backstory.

A roleplaying feature is an explicitly justified unique way of interacting with the world or its people, based on your background type. A roleplaying feature is, at its core, a story writing tool. User:Kydo has coined the term 'creativity paintbrush' to describe the actual nature of a roleplaying feature. Of particular importance, the types of stories we tell through D&D are called adventures. A roleplaying feature should either send players on adventures, or at least add something to their adventures. A good example of this is Antiquarian (5e Background). In a way, a roleplaying feature is just as much for the DM as it is for the PC, giving the characters hooks the DM can grab on to, rather than having to rely entirely on PC fishing techniques.

Regarding the 3 pillars of adventure[12], roleplaying features typically focus on either socialization or exploration. No roleplaying feature should ever provide any explicitly mechanical effects. No bonuses or penalties to any roles, no advantage or disadvantage, no forced attacks, no resistances or weaknesses, no bonus damage, no extra HP, no AC bonuses, no speed changes, no time travel, no advantage modifiers, no unique skill checks, no immunities, none of that kind of stuff! While it may be possible to indirectly work a roleplaying feature into a combat advantage, or to use sideways logic to invent a combat use for it, no roleplaying feature should ever have direct combat benefits. For example, a soldier may use their rank to requisition equipment or services from allied military men. If the DM lets you play a retired war-hero general, your rank could be used to acquire military services of great quantity and quality, possibly leading to a significant combat advantage. You had to get a good rank, and find a good situation to take advantage of it in order to do that, all requiring the cooperation of the DM, but it could be done. Now, it may be possible to write a combat oriented roleplaying feature, which allows the player to roleplay during combat in an interesting and unique way, without providing combat advantages- but we have yet to see an example of it.

As such, it can be deceptively difficult to write a good roleplaying feature. You need to have a good grasp of abstract play- that part of roleplaying that doesn't involve the dice or the numbers. If you want to get a feel for what we're talking about, try playing a game of D&D by avoiding the dice as much as possible. Use logic and creativity to avoid combat and otherwise overcome obstacles using your brains rather than your numbers. That is the realm of the game a roleplaying feature should exist and operate within.

When designing a roleplaying feature, try to focus on one of these key objectives:

- Getting the player to interact with the DM in an interesting way. Example: Mystic (5e Background)

- Getting the player to interact with other players in an interesting way. Example: Doctor (5e Background)

- Letting the character interact with their environment in an interesting way. Example: Psychic (5e Background)

- Letting the character interact with other characters in an interesting way. Example: Afflicted (5e Background)

- All of the above. Example: Unknown (5e Background)

Finally, and this is the hardest part of designing a roleplaying feature, it must also be useful to the player. That can be very hard to do without creating mechanical systems within it. It can be done. Read the examples in the PHB, and look for other officially published backgrounds if you're still unsure. Look for well-written backgrounds here on the wiki, like the ones linked as examples in this guide, for ideas on how background features can be tweaked or invented. A great example is Squire (5e Background), which has two different feature options, each of which is wholly unique!

Alternate Feature[edit]

Although in the corebooks these are listed after the background's characteristics, this leads to some weird formatting issues in the publication which make that section difficult to read, and cause the alternate features to be rather easily overlooked. To avoid the mistakes of the developers, we put alternative features as sub-sections to the main feature, making them clear and available to players and DMs alike. You can give a background as many alternate features as you like, but please try to keep these features tightly in-line with the theme of your background. The best use of alternative background options, is to incorporate as much of your theme as possible, not to make your background as desirable or as accessible as possible.

Suggested Characteristics[edit]

You should give an overview of the general nature of the background, and how it typically affects people. This leading paragraph should give players enough information so that they, and their DM, could create new characteristics for themselves during character creation, rather than trying to guess at what is appropriate, or being strictly restrained to the features given. When writing characteristics, always write material which gives players a reason to interact with the game, DM, players, or characters. Never write a characteristic which acts as a 'dead-end' to play. Dogmatic, antisocial, and explicitly destructive characteristics, for example, will almost certainly be removed by other editors upon review. Note that the tables are not strict, you can edit them to have pretty much any number of items. However, it is advisable to keep them restricted to the standard die-sizes: d4, d6, d8, d10, d12, or d20, so that players can still roll randomly for their characteristics if they want to. The ultimate goal of the characteristics you give a character, is to make them a round character in the literary sense of the term, rather than just a mechanical tool or vehicle through which a player interacts with the game. The objective is to avoid shallow game systems, and instead encourage complex, interesting, character-driven stories.

- Traits

- Traits are personality and behavior quirks which make them behave in a unique and interesting way. They exist almost entirely for the player's benefit, as a guideline for how to play their character, kind of like alignment, but even more loose. They include accomplishments, attitudes, voices, habits, preferences, tics, interests, mannerisms, feelings, disposition, and behavioral quirks. They may be justified or not, and can sometimes be key motivators behind the way a character thinks. For example, one of the guild artisan's traits is 'I believe anything worth doing is worth doing right, [...]' which would cause him to solve problems very differently than, say, a folk hero[13] with the trait, 'Thinking is for other people. I prefer action.' It may put them at odds, or it may not- it would be up to the players to find a way to reconcile their different approaches, and THAT is the kind of thing traits are supposed to do! The potential discussion about different ways of solving a problem would never have occurred, had the players not set out specific guiding behaviors to drive their characters! Keep in mind that characters get two personality traits, so avoid making incompatible traits on your list. For example, 'I'm a coward' and 'I'm the bravest man in my hometown' are hard to justify when paired.

- Ideals

- Ideals are specific motivations. They are the actual guiding principals that the character values most over anything else. Ideals are typically keyed to a specific alignment, but may also be unaligned. Interesting things can happen when a character of one alignment chooses an ideal which is not in accordance with that. It can make for dynamic and interesting characters, so avoid the laziness of just making every ideal 'unaligned'. Ideals can be used by the DM to motivate characters toward achieving certain goals, or to create tension between the players and world, or between the players themselves, by presenting them with challenges which conflict with their ideals. Ideals are one of the most powerful hooks a character can have, because they can be used extensively by both the player and DM.

- Bonds

- It doesn't say it in the core books, but a bond is a tool. It is a way for the player and DM to work together to weave their character's backstory into the setting. In a more aggressive sense, it is a way for the player to metaphorically 'sink their teeth into the setting' or 'set down roots in the world'. It is a way of connecting the character, and thus the player, to the setting at hand, and therefore give them a reason to care about what's happening in the game. Bonds are an extremely complex character hook, and can have all sorts of intricate effects on the game. Bonds which give a character family, friends, or enemies, may prompt the DM to create NPCs to represent them, in order to incorporate them into the game. The same can be said of bonds which link you to unique items or locations in the world, encouraging the DM to create those things. Bonds which give the character a specific goal, like finding a macguffin, or achieving some sort of greatness, are wonderful motivating forces. Bonds can be turned on their heads and have a negative, or repulsive effect though, almost like a flaw! For example, a bond which makes the PC devoted to their local lord may turn into a flaw if the local lord is currently an oppressive tyrant! It may motivate them to depose that tyrant in order to enthrone what the player sees as the 'rightful' lord, or to abandon their current homeland, or possibly even default to the enemy if the table is running that kind of game! Bonds have massive potential. One must be careful, however, with bonds which can be broken. A tie to a specific person, place, or thing is a risky thing to have- that person can be killed, that place can be conquered, and that thing can be destroyed. Depending on what the noun was, this can have terrible consequences for a character, and a player who is emotionally invested in their character may actually get their feelings hurt if they were not on board with such a thing.

- Flaws

- Read the PHB description of what a flaw[14] is. In addition to that, know the following: Character flaws should not be written such that a character would be encouraged to just stop dead in their tracks, or turn away from the story/adventure/party. Flaws may, at most, complicate a situation, or introduce new problems to overcome. Also, a flaw should be designed as something which can cause the character to become a dynamic character in the literary sense of the term. Perhaps they'll one day overcome their flaw and become a better person for it! Or maybe their flaw will get the better of them, and force them to change their ideals, or break a bond! Flaws are more than just negative characteristics or situational complications. They have the potential to describe, not just who your character is today, but who they could be in the future!

References[edit]

- ↑PHB pp.140

- ↑PHB pp.131

- ↑PHB pp.139

- ↑(PHB pp.147-148)

- ↑PHB pp.136

- ↑PHB pp.135-136

- ↑PHB pp.129

- ↑PHB pp.129

- ↑PHB pp.128

- ↑PHB pp.132

- ↑PHB pp.134

- ↑PHB pp.8

- ↑PHB pp.131

- ↑PHB p.124

Back to Main Page → 5e Homebrew → 5e Backgrounds

The D&D Dungeon Masters Guide is out now, and it’s a very cool resource filled with lots of new rules for treasure, magic items, world building, new downtime activities, and optional rules! Also, my name is in the play-tester credits, so that’s pretty fun :).

Anyway, instead of doing something ridiculous, like review an entire book, I’d like to focus on one specific element I found interesting, the rules for running a business during your downtime!

Building A Background 5e Dmg Free

The idea of running a business and making extra money during downtime is pretty appealing. It’s a great way to engage with the campaign world, a fun “simulationist” way to make money, and it opens up some cool adventure hooks for the DM. For example, maybe some mysterious cloaked figures show up at your Inn, clearly wounded and seeking shelter for the night, OR maybe a group of bumbling first level adventures meet up for the first time, planning a raid on a dragon lair that will surely result in their deaths!

However, running a business is a tricky mechanic to get right. You probably don’t want it to be TOO profitable, or else your PCs will be scratching their heads, wondering why they ever go on adventures. Conversely, if it doesn’t really make you any money, why even bother? Sure, running an Inn sounds cool, but if it’s not profitable, maybe you’re better off spending your character’s time elsewhere.

The folks at Wizards of the Coast gave running a business a decent shot that may work for casual play, but unfortunately it suffers from a few serious flaws when you dig into it:

- Running a big business is less profitable than running a small business: If you look at the table for running a business, you’ll see that lower results penalize you by forcing you to pay some percentage of your upkeep every day you spent running a business. Your upkeep can range from 5SP a day for a farm to 10GP a day for a trading post. That makes sense. If your business does poorly, you still have to pay your workers and keep your property in shape. What is pretty counter-intuitive, however, is that if you roll higher on the table, you roll a set amount of dice to determine your profit. This profit is in the same range no matter the size of your business. So a small farm makes the same profit as a large inn, but since the large inn has an upkeep that is 20 times larger, you’ll end up making a lot less money overall since it will hurt a lot more when you roll poorly and need to pay that upkeep.

- You make more money per day if you run a business for one day compared to 30 days: You get a bonus to your roll for every day you spend running a business. If you spend one day running a business, you get a +1% to your roll, where as if you spend 30 days running a business, you get a +30% to your roll. So on the surface, running a business for 30 days seems like it gives you a big advantage. However, if you crunch the numbers, you’ll find that it is vastly more profitable for your time to run a business for one day compared to 30 days. Sure, you make more money, but not enough to justify all the extra time spent. For example, if you spend one day running an Inn, you should expect to make about 13GP on average. If you run that same Inn for 30 days, you should expect to make about 26GP on average. So you’ve about doubled your profit for 30X the work! Clearly any player who can get away with it will try to game the system by making a roll every day for running a business.

- You pay upkeep on your business while you are away: On the surface, this isn’t too surprising. The property still needs to be maintained, and you’re going to need staff to keep everything running, but having this requirement means that for most campaigns, owning a business is a money losing proposition. Imagine a campaign where the PCs spend half their time in downtime and half their time traveling and going on adventures. That doesn’t seem too unusual. In such a campaign, the PC would spend 10GP on upkeep for every day spent adventuring and would make about 13GP for every day spent running their Inn. So technically, they are making a profit, but it is pretty thin, especially since they are probably spending 1GP to cover their lifestyle expenses every day they run their Inn. Now, imagine a campaign where the DM is constantly putting challenges in front of the PCs, forcing them to adventure frequently and travel across the world fighting evil. Now, they are only spending 1 day out of every 4 in downtime. Suddenly, the PC is losing A LOT of money running that Inn. For every 13GP they make on average, they are losing 30GP!

Building A Background 5e Dmg Download

With all that in mind, I put together the following house rules:

- Every week, you make a roll to see how much money your business makes (or loses). You make this roll regardless of whether you are spending your downtime running the business or not. One of the NPCs on your staff is assumed to be managing the business if your PC is not available. The DM may elect to make this roll in secret and inform you of the results when you return from adventuring. Absent other factors, the DM determines how trustworthy the NPC is, so PCs are advised to hire NPCs they already trust to run their business for them to avoid embezzlement.

- Replace the 61-80, 81-90 and 91+ results with the following:

61-80: You cover your upkeep and make 100% of your upkeep each day in profits (since businesses make a roll every week, you are multiplying your upkeep times 7).

81-90: You cover your upkeep and make 200% of your upkeep each day in profits.

91+: You cover your upkeep and make 300% of your upkeep each day in profits. - If you spend a week of downtime running your business, you get a +10 bonus on your roll that week. If you only spend a few days running the business during the week, you get a +1% bonus for every day you spent running the business (so it’s much more efficient to dedicate an entire week).

- As per normal rules, if you roll poorly and are required to pay upkeep but elect not to do so, subsequent rolls take a -10 penalty until you pay your debt. This effect is cumulative, so if you fail to pay your upkeep two times, you take a -20 on the roll, and so on. A PC may elect to leave funds behind to pay their debts if the business loses money while they are away; again if the NPC managing your business is not trustworthy, the DM may determine that they abscond with the money (tracking down an unscrupulous NPC could be an adventure in itself!).

- The DM may grant other temporary or permanent bonuses or penalties to these rolls as makes sense for the story. For example, perhaps one week there is an important festival in the town, and so the DM grants a +10 bonus. Or maybe a plague hits the town, and so the DM gives a -10 penalty. Alternatively, if an important rival is eliminated or a lucrative trade deal is established, the DM may grant a +5 or +10 bonus to rolls as long as that bonus remains in effect (which could be indefinitely).

If you crunch the numbers on these house rules, you’ll find that, absent any other factors, all businesses are profitable even without direct management. A farm makes about 1GP a week on average absent any management, and a rural Inn makes between 15-20GP a week on average. Of course, one wrong turn can send a business spiraling into the red. A single -10 modifier from an unpaid debt or unfortunate turn of events (perhaps goblins are attacking nearby trade routes) will turn a marginally profitable business into an unprofitable one, so PCs must remain vigilant to protect against any threats that arise through the course of play (or the DM’s whim).

If PCs are buying their businesses outright instead of, say, inheriting an Inn, they’ll find that absent direct management, they’ll recoup their investment within 4-5 years, which feels about right and isn’t too far from what you’d expect running a 7-11 in the real world! If they run the business non-stop or secure bonuses in other ways (such as lucrative trade deals), they can easily cut this time in half. In D&D terms, this may seem rather slow, but hey, there is SOME prestige to owning your own Inn or Trade-post, and you can always sell the property at a later date to get your money back (assuming you can find a buyer).

These rules can also be applied to running a barony or even an entire kingdom. As long as the manors and castles the PCs build or acquire come with the lands and rights to taxation appropriate to their station, you can factor in their upkeep and treat them like running any other business. Obviously, this doesn’t mean the PCs can spend 500K GP to build a palace in the wilderness and suddenly expect to start raking in the cash, but if the PCs are granted land or spend much of the campaign carving out their own little kingdom, I think it would be quite appropriate and a lot of fun. Bonuses and penalties to rolls take on a new meaning at this scale; suddenly a -10 negative represents a blight across the land or a war with a powerful kingdom that is taking its toll on the populace. A +10 bonus might represent a recent discovery of gold in mountains within the kingdom’s domain or a recent trade agreement with an exotic and faraway land.

This system is quite abstract, but I think it gives most DMs and Players the flexibility they need to fit it to a variety of different businesses and situations, including plenty of room for game events and PC actions to affect the development of the business. It’s also quite easy to manage, requiring one roll per game week and keeping track of a handful of modifiers (at most) and the current profit or debt of the business. I’m really excited to try it out in my campaign. I’d love to hear how it works for you, dear reader!